John Nolen’s Plan for San Diego

This post is part of SACRPH’s spotlight on the host city of its 2024 conference. To read more about the conference, click here.

By Bruce Stephenson

In 1907, John Nolen was commissioned to prepare San Diego’s first comprehensive plan, an “illustration of the awakening of American cities to the imperative need for greater foresight, skill, and experience in city-making,” Nolen wrote. This pioneering work documents the duties of the novice planning profession: land subdivision, siting of civic buildings, designing park systems and transportation networks, and addressing public health, and social justice.

Nolen had recently completed his first city plan for Roanoke, Virginia. Racial equality informed this commission, but San Diego’s civic leaders had a different focus, tourism. In planning an American Riviera, Nolen designed a “pleasure city,” an American Riviera, to model a future that would be “determined less by what people do in the few hours they are ‘officially at work’ than in their many hours of free time,” he predicted. Nolen believed recreation bred virtue and good health, and he planned San Diego on this ideal. The project was a challenge. Outside of the roughhewn 1,400-acre City Park (renamed Balboa Park), there were “no wide and impressive business streets, practically no open spaces in the heart of the city, no worthy sculpture.” The basic elements of a park system—parkways, neighborhood parks, and playgrounds—were missing, and the city’s potential would be lost unless without a plan, a point Nolen re-iterated in a flurry of lectures that left him feeling as if he had “spoken with every citizen in the county.”

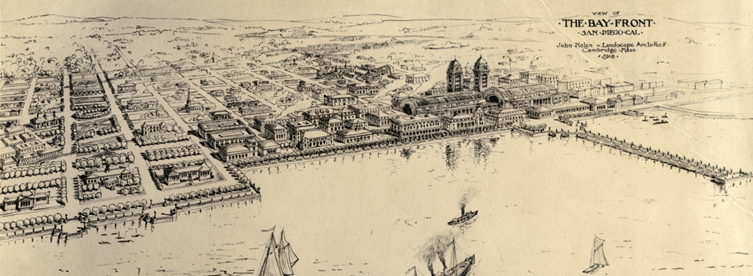

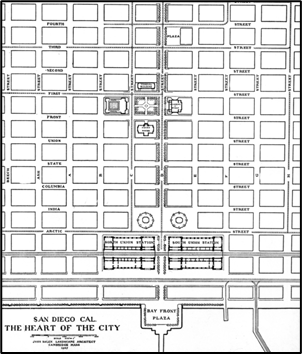

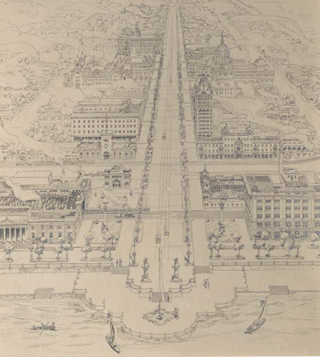

Nolen envisioned a modern “pleasure city” to rival the French Riviera. Bay Front Plaza was the centerpiece of a system of promenades and parks, a definitive public space offering stunning views of the Pacific Ocean. Following Beaux-Arts protocol, a boulevard connected Bay Plaza to a civic center half a mile away. This alignment was both functional and symbolic, placing the seat of government on axis with a grand plaza sited to view a sublime nature.

The “heart of downtown” was the focal point for a wide-ranging park system. Parkways linked Bay Plaza to preserves on Mount Soledad, the foothills overlooking Mission Valley, and a series of forest remnants, with Torrey Pines Reserve being the most significant. Located twenty miles north of the downtown, it was home to the rare species Pinus torreyana, which thrives on cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean. The long needles and distinctive cones Nolen photographed give the tree a graceful picturesque form that now defines the landscape of Torrey Pines State Park.

In 1926, Nolen updated his 1907 plan. By the New Deal, “the Nolen Plan is a civic slogan,” a city commissioner wrote. The federal government funded harbor improvements, highway connections, and two major parks in conformance with Nolen’s 1926 city plan. The New Deal also underwrote the construction of civic buildings (below) on the site Nolen identified in both his 1908 and 1926 plans. “Today the dream of the Boston city planner is coming true,” the Christian Science Monitor reported in 1934. Three three years later, San Diego was designated a prototype for programming and financing of public works projects. Today, the San Diego chapter of the American Institute of Architects confers the John Nolen Award, his plans still inform public debate, and the Nolen, a rooftop establishment in the historic downtown, is a feted destination.